Saturday, July 01, 2006

When Do We Publish a Secret?

SINCE Sept. 11, 2001, newspaper editors have faced excruciating choices in covering the government's efforts to protect the country from terrorist agents. Each of us has, on a number of occasions, withheld information because we were convinced that publishing it could put lives at risk. On other occasions, each of us has decided to publish classified information over strong objections from our government.

Last week our newspapers disclosed a secret Bush administration program to monitor international banking transactions. We did so after appeals from senior administration officials to hold the story. Our reports — like earlier press disclosures of secret measures to combat terrorism — revived an emotional national debate, featuring angry calls of "treason" and proposals that journalists be jailed along with much genuine concern and confusion about the role of the press in times like these.

We are rivals. Our newspapers compete on a hundred fronts every day. We apply the principles of journalism individually as editors of independent newspapers. We agree, however, on some basics about the immense responsibility the press has been given by the inventors of the country.

Make no mistake, journalists have a large and personal stake in the country's security. We live and work in cities that have been tragically marked as terrorist targets. Reporters and photographers from both our papers braved the collapsing towers to convey the horror to the world.

We have correspondents today alongside troops on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan. Others risk their lives in a quest to understand the terrorist threat; Daniel Pearl of The Wall Street Journal was murdered on such a mission. We, and the people who work for us, are not neutral in the struggle against terrorism.

But the virulent hatred espoused by terrorists, judging by their literature, is directed not just against our people and our buildings. It is also aimed at our values, at our freedoms and at our faith in the self-government of an informed electorate. If the freedom of the press makes some Americans uneasy, it is anathema to the ideologists of terror.

Thirty-five years ago yesterday, in the Supreme Court ruling that stopped the government from suppressing the secret Vietnam War history called the Pentagon Papers, Justice Hugo Black wrote: "The government's power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of the government and inform the people."

As that sliver of judicial history reminds us, the conflict between the government's passion for secrecy and the press's drive to reveal is not of recent origin. This did not begin with the Bush administration, although the polarization of the electorate and the daunting challenge of terrorism have made the tension between press and government as clamorous as at any time since Justice Black wrote.

Our job, especially in times like these, is to bring our readers information that will enable them to judge how well their elected leaders are fighting on their behalf, and at what price.

In recent years our papers have brought you a great deal of information the White House never intended for you to know — classified secrets about the questionable intelligence that led the country to war in Iraq, about the abuse of prisoners in Iraq and Afghanistan, about the transfer of suspects to countries that are not squeamish about using torture, about eavesdropping without warrants.

As Robert G. Kaiser, associate editor of The Washington Post, asked recently in the pages of that newspaper: "You may have been shocked by these revelations, or not at all disturbed by them, but would you have preferred not to know them at all? If a war is being waged in America's name, shouldn't Americans understand how it is being waged?"

Government officials, understandably, want it both ways. They want us to protect their secrets, and they want us to trumpet their successes. A few days ago, Treasury Secretary John Snow said he was scandalized by our decision to report on the bank-monitoring program. But in September 2003 the same Secretary Snow invited a group of reporters from our papers, The Wall Street Journal and others to travel with him and his aides on a military aircraft for a six-day tour to show off the department's efforts to track terrorist financing. The secretary's team discussed many sensitive details of their monitoring efforts, hoping they would appear in print and demonstrate the administration's relentlessness against the terrorist threat.

How do we, as editors, reconcile the obligation to inform with the instinct to protect?

Sometimes the judgments are easy. Our reporters in Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, take great care not to divulge operational intelligence in their news reports, knowing that in this wired age it could be seen and used by insurgents.

Often the judgments are painfully hard. In those cases, we cool our competitive jets and begin an intensive deliberative process.

The process begins with reporting. Sensitive stories do not fall into our hands. They may begin with a tip from a source who has a grievance or a guilty conscience, but those tips are just the beginning of long, painstaking work. Reporters operate without security clearances, without subpoena powers, without spy technology. They work, rather, with sources who may be scared, who may know only part of the story, who may have their own agendas that need to be discovered and taken into account. We double-check and triple-check. We seek out sources with different points of view. We challenge our sources when contradictory information emerges.

Then we listen. No article on a classified program gets published until the responsible officials have been given a fair opportunity to comment. And if they want to argue that publication represents a danger to national security, we put things on hold and give them a respectful hearing. Often, we agree to participate in off-the-record conversations with officials, so they can make their case without fear of spilling more secrets onto our front pages.

Finally, we weigh the merits of publishing against the risks of publishing. There is no magic formula, no neat metric for either the public's interest or the dangers of publishing sensitive information. We make our best judgment.

When we come down in favor of publishing, of course, everyone hears about it. Few people are aware when we decide to hold an article. But each of us, in the past few years, has had the experience of withholding or delaying articles when the administration convinced us that the risk of publication outweighed the benefits. Probably the most discussed instance was The New York Times's decision to hold its article on telephone eavesdropping for more than a year, until editors felt that further reporting had whittled away the administration's case for secrecy.

But there are other examples. The New York Times has held articles that, if published, might have jeopardized efforts to protect vulnerable stockpiles of nuclear material, and articles about highly sensitive counterterrorism initiatives that are still in operation. In April, The Los Angeles Times withheld information about American espionage and surveillance activities in Afghanistan discovered on computer drives purchased by reporters in an Afghan bazaar.

It is not always a matter of publishing an article or killing it. Sometimes we deal with the security concerns by editing out gratuitous detail that lends little to public understanding but might be useful to the targets of surveillance. The Washington Post, at the administration's request, agreed not to name the specific countries that had secret Central Intelligence Agency prisons, deeming that information not essential for American readers. The New York Times, in its article on National Security Agency eavesdropping, left out some technical details.

Even the banking articles, which the president and vice president have condemned, did not dwell on the operational or technical aspects of the program, but on its sweep, the questions about its legal basis and the issues of oversight.

We understand that honorable people may disagree with any of these choices — to publish or not to publish. But making those decisions is the responsibility that falls to editors, a corollary to the great gift of our independence. It is not a responsibility we take lightly. And it is not one we can surrender to the government.

— DEAN BAQUET, editor, The Los Angeles Times, and BILL KELLER, executive editor, The New York Times

Friday, June 30, 2006

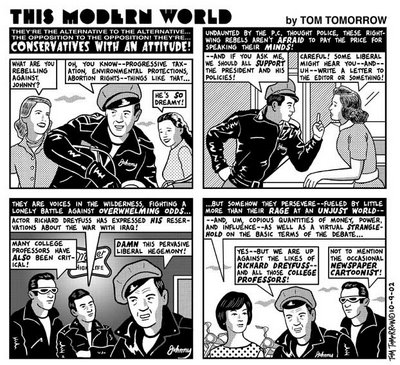

This Modern World

Feds Silence Another Whistleblower

A U.S. government whistleblower fired for trying to subpoena a politically connected Wall Street executive during an insider trading investigation was muzzled by his former agency during Congressional testimony this week. The former Securities and Exchange Commission attorney was warned by agency officials to comply with his “ethical obligations,” which basically means to keep quiet.

Apparently, the SEC, the government’s top cop for Wall Street, wants to eliminate evidence of how it covered up for a powerful and politically connected CEO named John Mack,

who, among other things, is a major fundraiser for President George W. Bush. In fact, Mack was one of the nine Wall Street “Rangers” who raised at least $200,000 for Bush’s re-election campaign.

When the insider trading investigation of major hedge fund Pequot Capitol pointed to the president’s deep-pocketed pal, agency officials warned the lead investigator on the case, former SEC attorney Gary Aguirre, to back off. Pequot had made a profit of $18 million based on illegal insider trading and Aguirre had gathered lots of evidence—including millions of e-mails, telephone records and credit card receipts—pointing to Mack as the source of the tip.

Mack is currently the chief executive of Morgan Stanley, one of the nation’s largest securities firm, but at the time he held the same position at another company. Besides his powerful buddy in the White House, he is also good friends with the head of Pequot, a man named Arthur Samberg. The fired whistleblower said that high-ranking SEC officials quashed his probe into Pequot as soon as his leads got too close to the politically connected Mack.

Upon getting fired, Aguirre wrote a damaging 18-page letter to a pair of senators and the chairman of the Senate Banking and Finance Committee. It details how SEC officials halted his investigation and forbid him from talking to Mack. He also writes that "it is not surprising that the US Office of Management and Budget gave SEC enforcement its lowest performance assessment."

Republicans slow Voting Rights Act renewal

By Amanda Beck

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Prospects for a swift renewal of the Voting Rights Act faded on Thursday as lawmakers called for new congressional hearings on the landmark civil rights law first approved in 1965.

The House leadership had expected an easy 25-year extension of the act last week but southern Republicans rebelled, objecting that their states would be subjected to special scrutiny based on the legacy of discrimination from the 1960s.

The Voting Rights Act is designed to end discrimination at the polls and has been renewed four times. If Congress does not act again, parts of it will expire in 2007.

Lawmakers are divided on several issues, including whether districts should supply bilingual voting ballots and whether hearings should examine the impact of this week's Supreme Court ruling on Texas redistricting.

House Majority Leader John Boehner, an Ohio Republican, said Congress would return to the matter after a weeklong July 4 recess. Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, a California Democrat, said party members were "holding our fire and patiently waiting for the Republicans to work out their politics."

The Senate has not yet taken up the bill.

15 years

THE HIDDEN POWER

Posted 2006-06-26

On December 18th, Colin Powell, the former Secretary of State, joined other prominent Washington figures at FedEx Field, the Redskins’ stadium, in a skybox belonging to the team’s owner. During the game, between the Redskins and the Dallas Cowboys, Powell spoke of a recent report in the Times which revealed that President Bush, in his pursuit of terrorists, had secretly authorized the National Security Agency to eavesdrop on American citizens without first obtaining a warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, as required by federal law. This requirement, which was instituted by Congress in 1978, after the Watergate scandal, was designed to protect civil liberties and curb abuses of executive power, such as Nixon’s secret monitoring of political opponents and the F.B.I.’s eavesdropping on Martin Luther King, Jr. Nixon had claimed that as President he had the “inherent authority” to spy on people his Administration deemed enemies, such as the anti-Vietnam War activist Daniel Ellsberg. Both Nixon and the institution of the Presidency had paid a high price for this assumption. But, according to the Times, since 2002 the legal checks that Congress constructed to insure that no President would repeat Nixon’s actions had been secretly ignored.

According to someone who knows Powell, his comment about the article was terse. “It’s Addington,” he said. “He doesn’t care about the Constitution.” Powell was referring to David S. Addington, Vice-President Cheney’s chief of staff and his longtime principal legal adviser. Powell’s office says that he does not recall making the statement. But his former top aide, Lawrence Wilkerson, confirms that he and Powell shared this opinion of Addington.

Most Americans, even those who follow politics closely, have probably never heard of Addington. But current and former Administration officials say that he has played a central role in shaping the Administration’s legal strategy for the war on terror. Known as the New Paradigm, this strategy rests on a reading of the Constitution that few legal scholars share—namely, that the President, as Commander-in-Chief, has the authority to disregard virtually all previously known legal boundaries, if national security demands it. Under this framework, statutes prohibiting torture, secret detention, and warrantless surveillance have been set aside. A former high-ranking Administration lawyer who worked extensively on national-security issues said that the Administration’s legal positions were, to a remarkable degree, “all Addington.” Another lawyer, Richard L. Shiffrin, who until 2003 was the Pentagon’s deputy general counsel for intelligence, said that Addington was “an unopposable force.”

The overarching intent of the New Paradigm, which was put in place after the attacks of September 11th, was to allow the Pentagon to bring terrorists to justice as swiftly as possible. Criminal courts and military courts, with their exacting standards of evidence and emphasis on protecting defendants’ rights, were deemed too cumbersome. Instead, the President authorized a system of detention and interrogation that operated outside the international standards for the treatment of prisoners of war established by the 1949 Geneva Conventions. Terror suspects would be tried in a system of military commissions, in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, devised by the executive branch. The Administration designated these suspects not as criminals or as prisoners of war but as “illegal enemy combatants,” whose treatment would be ultimately decided by the President. By emphasizing interrogation over due process, the government intended to preëmpt future attacks before they materialized. In November, 2001, Cheney said of the military commissions, “We think it guarantees that we’ll have the kind of treatment of these individuals that we believe they deserve.”

Yet, almost five years later, this improvised military model, which Addington was instrumental in creating, has achieved very limited results. Not a single terror suspect has been tried before a military commission. Only ten of the more than seven hundred men who have been imprisoned at Guantánamo have been formally charged with any wrongdoing. Earlier this month, three detainees committed suicide in the camp. Germany and Denmark, along with the European Union and the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, have called for the prison to be closed, accusing the United States of violating internationally accepted standards for humane treatment and due process. The New Paradigm has also come under serious challenge from the judicial branch. Two years ago, in Rasul v. Bush, the Supreme Court ruled against the Administration’s contention that the Guantánamo prisoners were beyond the reach of the U.S. court system and could not challenge their detention. And this week the Court is expected to deliver a decision in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, a case that questions the legality of the military commissions.

For years, Addington has carried a copy of the U.S. Constitution in his pocket; taped onto the back are photocopies of extra statutes that detail the legal procedures for Presidential succession in times of national emergency. Many constitutional experts, however, question his interpretation of the document, especially his views on Presidential power. Scott Horton, a professor at Columbia Law School, and the head of the New York Bar Association’s International Law committee, said that Addington and a small group of Administration lawyers who share his views had attempted to “overturn two centuries of jurisprudence defining the limits of the executive branch. They’ve made war a matter of dictatorial power.” The historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., who defined Nixon as the extreme example of Presidential overreaching in his book “The Imperial Presidency” (1973), said he believes that Bush “is more grandiose than Nixon.” As for the Administration’s legal defense of torture, which Addington played a central role in formulating, Schlesinger said, “No position taken has done more damage to the American reputation in the world—ever.”

Bruce Fein, a Republican legal activist, who voted for Bush in both Presidential elections, and who served as associate deputy attorney general in the Reagan Justice Department, said that Addington and other Presidential legal advisers had “staked out powers that are a universe beyond any other Administration. This President has made claims that are really quite alarming. He’s said that there are no restraints on his ability, as he sees it, to collect intelligence, to open mail, to commit torture, and to use electronic surveillance. If you used the President’s reasoning, you could shut down Congress for leaking too much. His war powers allow him to declare anyone an illegal combatant. All the world’s a battlefield—according to this view, he could kill someone in Lafayette Park if he wants! It’s got the sense of Louis XIV: ‘I am the State.’ ” Richard A. Epstein, a prominent libertarian law professor at the University of Chicago, said, “The President doesn’t have the power of a king, or even that of state governors. He’s subject to the laws of Congress! The Administration’s lawyers are nuts on this issue.” He warned of an impending “constitutional crisis,” because “their talk of the inherent power of the Presidency seems to be saying that the courts can’t stop them, and neither can Congress.”

The former high-ranking lawyer for the Administration, who worked closely with Addington, and who shares his political conservatism, said that, in the aftermath of September 11th, “Addington was more like Cheney’s agent than like a lawyer. A lawyer sometimes says no.” He noted, “Addington never said, ‘There is a line you can’t cross.’ ” Although the lawyer supported the President, he felt that his Administration had been led astray. “George W. Bush has been damaged by incredibly bad legal advice,” he said.

David Addington is a tall, bespectacled man of forty-nine, who has a thickening middle, a thatch of gray hair, and a trim gray beard, which gives him the look of a sea captain. He is extremely private; he keeps the door of his office locked at all times, colleagues say, because of the national-security documents in his files. He has left almost no public paper trail, and he does not speak to the press or allow photographs to be taken for news stories. (He declined repeated requests to be interviewed for this article.)

In many ways, his influence in Washington defies conventional patterns. Addington doesn’t serve the President directly. He has never run for elected office. Although he has been a government lawyer for his entire career, he has never worked in the Justice Department. He is a hawk on defense issues, but he has never served in the military.

There are various plausible explanations for Addington’s power, including the force of his intellect and his personality, and his closeness to Cheney, whose political views he clearly shares. Addington has been an ally of Cheney’s since the nineteen-eighties, and has been referred to as “Cheney’s Cheney,” or, less charitably, as “Cheney’s hit man.” Addington’s talent for bureaucratic infighting is such that some of his supporters tend to invoke, with admiration, metaphors involving knives. Juleanna Glover Weiss, Cheney’s former press secretary, said, “David is efficient, discreet, loyal, sublimely brilliant, and, as anyone who works with him knows, someone who, in a knife fight, you want covering your back.” Bradford Berenson, a former White House lawyer, said, “He’s powerful because people know he speaks for the Vice-President, and because he’s an extremely smart, creative, and aggressive public official. Some engage in bureaucratic infighting using slaps. Some use knives. David falls into the latter category. You could make the argument that there are some costs. It introduces a little fear into the policymaking process. Views might be more candidly expressed without that fear. But David is like the Marines. No better friend—no worse enemy.” People who have sparred with him agree. “He’s utterly ruthless,” Lawrence Wilkerson said. A former top national-security lawyer said, “He takes a political litmus test of everyone. If you’re not sufficiently ideological, he would cut the ground out from under you.”

Another reason for Addington’s singular role after September 11th is that he offered legal certitude at a moment of great political and legal confusion, in an Administration in which neither the President, the Vice-President, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of State, nor the national-security adviser was a lawyer. (In the Clinton Administration, all these posts, except for the Vice-Presidency, were held by lawyers at some point.) Neither the Attorney General, John Ashcroft, nor the White House counsel, Alberto Gonzales, had anything like Addington’s familiarity with national-security law. Moreover, Ashcroft’s relations with the White House were strained, and he was left out of the inner circle that decided the most radical legal strategies in the war on terror. Gonzales had more influence, because of his longtime ties to the President, but, as an Administration lawyer put it, “he was an empty suit. He was weak. And he doesn’t know shit about the Geneva Conventions.” Participants in meetings in the White House counsel’s office, in the days immediately after September 11th, have described Gonzales sitting in a wingback chair, asking questions, while Addington sat directly across from him and held forth. “Gonzales would call the meetings,” the former high-ranking lawyer recalled. “But Addington was always the force in the room.” Bruce Fein said that the Bush legal team was strikingly unsophisticated. “There is no one of legal stature, certainly no one like Bork, or Scalia, or Elliot Richardson, or Archibald Cox,” he said. “It’s frightening. No one knows the Constitution—certainly not Cheney.”

Conventional wisdom holds that September 11th changed everything, including the thinking of Cheney and Addington. Brent Scowcroft, the former national-security adviser, has said of Cheney that he barely recognizes the reasonable politician he knew in the past. But a close look at the twenty-year collaboration between Cheney and Addington suggests that in fact their ideology has not changed much. It seems clear that Addington was able to promote vast executive powers after September 11th in part because he and Cheney had been laying the political groundwork for years. “This preceded 9/11,” Fein, who has known both men professionally for decades, said. “I’m not saying that warrantless surveillance did. But the idea of reducing Congress to a cipher was already in play. It was Cheney and Addington’s political agenda.”

Addington’s admirers see him as a selfless patriot, a workaholic defender of a purist interpretation of Presidential power—the necessary answer to threatening times. In 1983, Steve Berry, a Republican lawyer and lobbyist in Washington, hired Addington to work with him as the legislative counsel to the House Intelligence Committee; he has been a career patron and close friend ever since. He said, “I know him well, and I know that if there’s a threat he will do everything in his power, within the law, to protect the United States.” Berry added that Addington is acutely aware of the legal tensions between liberty and security. “We fought ourselves every day about it,” he recalled. But, he said, they concluded that a “strong national security and defense” was the first priority, and that “without a strong defense, there’s not much expectation or hope of having other freedoms.” He said that there is no better defender of the country than Addington: “I’ve got a lot of respect for the guy. He’s probably the foremost expert on intelligence and national-security law in the nation right now.” Berry has a daughter who works in New York City, and he said that when he thinks of her safety he appreciates the efforts that Addington has made to strengthen the country’s security. He said, “For Dave, protecting America isn’t just a virtue. It’s a personal mission. I feel safer just knowing he’s where he is.”

Berry said of his friend, “He’s methodical, conscientious, analytical, and logical. And he’s as straight an arrow as they come.” He noted that Addington refuses to let Berry treat him to a hamburger because it might raise issues of influence-buying—instead, they split the check. Addington, he went on, has a dazzling ability to recall the past twenty-five years’ worth of intelligence and national-security legislation. For many years, he kept a vast collection of legal documents in a library in his modest brick-and-clapboard home, in Alexandria, Virginia. One evening several years ago, lightning struck a nearby power line and the house caught fire; much of the archive burned. The fire started at around nine in the evening, and Addington, typically, was still in his office. His wife, Cynthia, and their three daughters were fine, but the loss of his extraordinary collection of papers and political memorabilia, Berry said, “was very hard for him to accept. All you get in this work is memorabilia. There is no cash. But he’s the type of guy who gets psychic benefit from going to work every day, making a difference.”

Though few people doubt Addington’s knowledge of national-security law, even his admirers question his political instincts. “The only time I’ve seen him wrong is on his political judgment,” a former colleague said. “He has a tin ear for political issues. Sometimes the law says one thing, but you have to at least listen to the other side. He will cite case history, case after case. David doesn’t see why you have to compromise.” Even Berry offered a gentle criticism: “His political skills can be overshadowed by his pursuit of what he feels is legally correct.”

Addington has been a hawk on national defense since he was a teen-ager. Leonard Napolitano, an engineer who was one of Addington’s close childhood friends, and whose political leanings are more like those of his sister, Janet Napolitano, the Democratic governor of Arizona, joked, “I don’t think that in high school David was a believer in the divine right of kings.” But, he said, Addington was “always conservative.”

The Addingtons were a traditional Catholic military family. They moved frequently; David’s father, Jerry, an electrical engineer in the Army, was assigned to a variety of posts, including Saudi Arabia and Washington, D.C., where he worked with the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As a teen-ager, Addington told a friend that he hoped to live in Washington himself when he grew up. Jerry Addington, a 1940 graduate of West Point who won a Bronze Star during the Second World War, also served in Korea and at the North American Air Defense Command, in Colorado; he reached the rank of brigadier general before he retired, in 1970, when David was thirteen. David attended public high school in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and his father began a second career, teaching middle-school math. His mother, Eleanore, was a housewife; the family lived in a ranch house in a middle-class subdivision. She still lives there; Jerry died in 1994. “We are an extremely close family,” one of Addington’s three older sisters, Linda, recalled recently. “Discipline was very important for us, and faith was very important. It was about being ethical—the right thing to do whether anyone else does it or not. I see that in Dave.” She was reluctant to say more. “Dave is most deliberate about his privacy,” she added.

Socially, Napolitano recalled, he and Addington were “the brains, or nerds.” Addington stood out for wearing black socks with shorts. He and his friends were not particularly athletic, and they liked to play poker all night on weekends, stopping early in the morning for breakfast. Their circle included some girls, until the boys found them “too distracting to our interest in cards,” Napolitano recalled.

When he and Addington were in high school, Napolitano said, the Vietnam War was in its final stages, and “there was a certain amount of ‘Challenge authority’ and alcohol and drugs, but they weren’t issues in our group.” Addington’s high-school history teacher, Irwin Hoffman, whom Napolitano recalled as wonderful, exacting, and “a flaming liberal,” said that Addington felt strongly that America “should have stayed and won the Vietnam War, despite the fact that we were losing.” Hoffman, who is retired, added, “The boy seemed terribly, terribly bright. He wrote well, and he was very verbal, not at all reluctant to express his opinions. He was pleasant and quite handsome. He also had a very strong sarcastic streak. He was scornful of anyone who said anything that was naïve, or less than bright. His sneers were almost palpable.”

Addington graduated in 1974, the year that Nixon resigned. In the aftermath of Watergate, liberal Democratic reformers imposed tighter restraints on the President and reined in the C.I.A., whose excesses were critiqued in congressional hearings, led by Senator Frank Church and Representative Otis Pike, that exposed details of assassination plots, coup attempts, mind-control experiments, and domestic spying. Congress passed a series of measures aimed at reinvigorating the system of checks and balances, including an expanded Freedom of Information Act and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the law requiring judicial review before foreign suspects inside the country could be wiretapped. It also created the House and Senate Intelligence Committees, which oversee all covert C.I.A. activities.

After high school, Addington pursued an ambition that he had had for years: to join the military. Rather than attending West Point, as his father had, he enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy, in Annapolis. But he dropped out before the end of his freshman year. He went home and, according to Napolitano, worked in a Long John Silver’s restaurant. “The academy wasn’t academically challenging enough for him,” Napolitano said.

Addington went to Georgetown University, graduating summa cum laude, in 1978, from the school of foreign service; he went on to earn honors at Duke Law School. After graduating, in 1981, he married Linda Werling, a graduate student in pharmacology. The marriage ended in divorce. His current wife, Cynthia, takes care of their three girls full-time.

Soon after leaving Duke, Addington started his first job, in the general counsel’s office at the C.I.A. A former top agency lawyer who later worked with Addington said that Addington strongly opposed the reform movements that followed Vietnam and Watergate. “Addington was too young to be fully affected by the Vietnam War,” the lawyer said. “He was shaped by the postwar, post-Watergate years instead. He thought the Presidency was too weakened. He’s a believer that in foreign policy the executive is meant to be quite powerful.”

These views were shared by Dick Cheney, who served as chief of staff in the Ford Administration. “On a range of executive-power issues, Cheney thought that Presidents from Nixon onward yielded too quickly,” Michael J. Malbin, a political scientist who has advised Cheney on the issue of executive power, said. Kenneth Adelman, who was a high-ranking Pentagon official under Ford, said that the fall of Saigon, in 1975, was “very painful for Dick. He believed that Vietnam could have been saved—maybe—if Congress hadn’t cut off funding. He was against that kind of interference.”

Jane Harman, the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, who has spent considerable time working with Cheney and Addington in recent years, believes that they are still fighting Watergate. “They’re focussed on restoring the Nixon Presidency,” she said. “They’ve persuaded themselves that, following Nixon, things went all wrong.” She said that in meetings Addington is always courtly and pleasant. But when it comes to accommodating Congress “his answer is always no.”

In a revealing interview that Cheney gave last December to reporters travelling with him to Oman, he explained, “I do have the view that over the years there had been an erosion of Presidential power and authority. . . . A lot of the things around Watergate and Vietnam both, in the seventies, served to erode the authority I think the President needs.” Further, Cheney explained, it was his express aim to restore the balance of power. The President needed to be able to act as Alexander Hamilton had described it in the Federalist Papers, with “secrecy” and “despatch”—especially, Cheney said, “in the day and age we live in . . . with the threats we face.” He added, “I believe in a strong, robust executive authority, and I think the world we live in demands it.”

At the C.I.A., where Addington spent two years, he focussed on curtailing the ability of Congress to interfere in intelligence gathering. “He was a rookie, plenty bright,” Frederick Hitz, another C.I.A. lawyer, who later became Inspector General, recalled. After the Church and Pike hearings, legislators came up with hundreds of pages of oversight recommendations, he said. “Addington was very pro-agency. He was trying to figure out how to comply with government oversight without getting hog-tied.” Addington viewed the public airings of the C.I.A.’s covert activities as “an absolute disaster,” Berry recalled. “We both felt that Congress did great harm by flinging open the doors to operational secrets.”

When Addington joined the C.I.A., it was directed by William J. Casey, who also regarded congressional constraints on the agency as impediments to be circumvented. His sentiment about congressional overseers was best captured during a hearing about covert actions in Central America, when he responded to tough questioning by muttering the word “assholes.” After Reagan’s election in 1980, the executive branch was dominated by conservative Republicans, while the House was governed by liberal Democrats. The two parties fought intensely over Central America; the Reagan Administration was determined to overthrow the leftist Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Using their constitutional authority over appropriations, the Democrats in Congress forbade the C.I.A. to spend federal funds to support the Contras, a rightist rebel group. But Casey’s attitude, as Berry recalled it, was “We’re gonna fund these freedom fighters whether Congress wants us to or not.” Berry, then the staff director for the Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee, asked Casey for help in fighting the Democrats. Soon afterward, Addington joined Berry on Capitol Hill.

When the Iran-Contra scandal broke, in 1986, it exposed White House arms deals and foreign fund-raising designed to help the anti-Sandinista forces in Nicaragua. Members of Congress were furious. Summoned to Capitol Hill, Casey lied, denying that funds for the Contras had been solicited from any foreign governments, although he knew that the Saudis, among others, had agreed to give millions of dollars to the Contras, at the request of the White House. Even within the Reagan Administration, the foreign funding was controversial. Secretary of State George Shultz had warned Reagan that he might be committing an impeachable offense. But, under Casey’s guidance, the White House went ahead with the plan; Shultz, having expressed misgivings, was not told. It was a bureaucratic tactic that Addington reprised after September 11th, when Powell was left out of key deliberations about the treatment of detainees. Lawrence Wilkerson, Powell’s aide, said that he was aware of Addington’s general strategy: “We had heard that, behind our backs, he was saying that Powell was ‘soft, but easy to get around.’ ”

The Iran-Contra scandal substantially weakened Reagan’s popularity and, eventually, seven people were convicted of seventeen felonies. Cheney, who was then a Republican congressman from Wyoming, worried that the scandal would further undercut Presidential authority. In late 1986, he became the ranking Republican on a House select committee that was investigating the scandal, and he commissioned a report on Reagan’s support of the Contras. Addington, who had become an expert in intelligence law, contributed legal research. The scholarly-sounding but politically outlandish Minority Report, released in 1987, argued that Congress—not the President—had overstepped its authority, by encroaching on the President’s foreign-policy powers. The President, the report said, had been driven by “a legitimate frustration with abuses of power and irresolution by the legislative branch.” The Minority Report sanctioned the President’s actions to a surprising degree, considering the number of criminal charges that resulted from the scandal. The report also defended the legality of ignoring congressional intelligence oversight, arguing that “the President has the Constitutional and statutory authority to withhold notifying Congress of covert actions under rare conditions.” And it condemned “legislative hostage taking,” noting that “Congress must realize . . . that the power of the purse does not make it supreme” in matters of war. In his December interview with reporters, Cheney proudly cited this document. “If you want reference to an obscure text, go look at the minority views that were filed in the Iran-Contra committee, the Iran-Contra report, in about 1987,” he said. “Part of the argument was whether the President had the authority to do what was done in the Reagan years.”

Addington and Cheney became a formidable team, but it was soon clear that Addington would not join Cheney as a politician. Adelman recalled Addington’s personality as “dour,” adding that, “unlike with Dick, I never saw much of a sense of humor. Cheney can be witty and funny. David is sober. I didn’t see him at social events much.” But, he added, “Dick wasn’t looking for friends at work. He was looking for performance. And David delivers. He’s efficient and dedicated. He’s a doer.” He went on, “Cheney’s not a lawyer, so he would defer to David on the law.”

In 1989, President George H. W. Bush appointed Cheney Secretary of Defense. Cheney hired Addington first as his special assistant and, later, as the Pentagon’s general counsel. At the Pentagon, Addington became widely known as Cheney’s gatekeeper—a stickler for process who controlled the flow of documents to his boss. Using a red felt-tipped pen, he covered his colleagues’ memos with comments before returning them for rewrites. His editing invariably made arguments sharper, smarter, and more firm in their defense of Cheney’s executive powers, a former military official who worked with him said.

At the Pentagon, Addington took a particular interest in the covert actions of the Special Forces. A former colleague recalled that, after attending a demonstration by Special Forces officers, he mocked the C.I.A., which was constrained by oversight laws. “This is how real covert operations are done,” he said. (After September 11th, the Pentagon greatly expanded its covert intelligence operations; these programs have less congressional oversight than those of the C.I.A.) Cheney, throughout his tenure as Defense Secretary, shared with Addington a pessimistic view of the Soviet Union. Both remained skeptical of Gorbachev long after the State Department, the national-security adviser, and the C.I.A. had concluded that he was a reformer. “They were always, like, ‘Whoa—beware the Bear!’ ” Wilkerson recalled. They immersed themselves in “continuity of government exercises”—studying with unusual intensity how the government might survive a nuclear attack. According to “Rise of the Vulcans,” a history of the period by James Mann, Cheney, more than once, spent the night in an underground bunker.

A decade later, when hijacked planes slammed into the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, Addington, perhaps more than anyone else in the U.S. government, was ready to act. During the Clinton Presidency, he had worked as a lawyer for various business interests, such as the American Trucking Associations, and in 1994 he had led an exploratory Presidential campaign for Cheney, who decided against running. Once Cheney became Vice-President, Addington helped oversee the transition, setting up the most powerful Vice-Presidency in America’s history. Addington’s high-school friend Leonard Napolitano said Addington told him that he and Cheney were merging the Vice-President’s office with the President’s into a single “Executive Office,” instead of having “two different camps.” Napolitano added, “David said that Cheney saw the Vice-President as the executive and implementer of the President.” Addington created a system to insure that virtually all important documents relating to national-security matters were seen by the Vice-President’s office. The former high-ranking Administration lawyer said that Addington regularly attended White House legal meetings with the C.I.A. and the National Security Agency. He received copies of all National Security Council documents, including internal memos from the staff. And, as a former top official in the Defense Department, he exerted influence over the legal office at the Pentagon, helping his protégé William J. Haynes secure the position of general counsel. A former national-security lawyer, speaking of the Pentagon’s legal office, said, “It’s obvious that Addington runs the whole operation.”

In the days after September 11th, a half-dozen White House lawyers had heated discussions about how to frame the Administration’s legal response to the attacks. Bradford Berenson, one of the participants, recalled how “raw” feelings were at the time: “There were thousands of bereaved American families. Everyone was expecting additional attacks. The only planes in the air were military. At a moment like that, there’s an intense focus on responsibility and accountability. Preventing another attack should always be within the law. But if you have to err on the side of being too aggressive or not aggressive enough, you’d err by being too aggressive.”

Berry said that Addington felt this keenly. “I’ve talked to David about this a little. Psychologically, it’s really taxing to read every day not about one or two but about a dozen, or two dozen, legitimate reports about efforts to take out U.S. citizens. . . . There’s a little bit of a bunker mentality that set in among some of the national-security-policy officials after 9/11.”

Almost immediately, other Administration lawyers noticed that Addington dominated the internal debates. His assumption, shared by other hard-line lawyers in the White House counsel’s office and in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, was that the criminal-justice system was insufficient to handle the threat from terrorism. The matter was settled without debate, Berenson recalled: “There was a consensus that we had to move from retribution and punishment to preëmption and prevention. Only a warfare model allows that approach.”

Richard Shiffrin, the former Pentagon lawyer, said that during a tense White House meeting held in the Situation Room just a few days after September 11th “all of us felt under a great deal of pressure to be willing to consider even the most extraordinary proposals. The C.I.A., the N.S.C., the State Department, the Pentagon, and the Justice Department all had people there. Addington was particularly strident. He’d sit, listen, and then say, ‘No, that’s not right.’ He was particularly doctrinaire and ideological. He didn’t recognize the wisdom of the other lawyers. He was always right. He didn’t listen. He knew the answers.” The details of the discussion are classified, Shiffrin said, but he left with the impression that Addington “doesn’t believe there should be co-equal branches.” Another participant recalled, “If you favored international law, you were in danger of being called ‘soft on terrorism’ by Addington.” He added that Addington’s manner in meetings was “very insistent and very loud.” Yet another participant said that, whenever he cautioned against executive-branch overreaching, Addington would respond brusquely, “There you go again, giving away the President’s power.”

Some of the protests from Democrats about the Administration’s legal arguments and some of the declarations of high principle from Republicans are mere partisan gestures. Both sides have changed their views about the need for a strong President, depending on whether they were in power. “It’s a matter of degree,” the liberal Princeton historian Sean Wilentz said. “War always expands the powers of the Presidency. And Presidents always overreach.” Lincoln infamously suspended habeas-corpus rights during the Civil War, locking up thousands of Confederate sympathizers without due process, and Franklin D. Roosevelt interned more than a hundred thousand innocent Japanese-Americans. “Someone said that this Administration is monarchical,” Wilentz added. “That’s just rhetoric. We’re not a dictatorship. At the same time, this White House has assumed powers for itself that no previous Administration has done.” Bush’s defenders frequently cite the example of Lincoln as a justification for placing national security above the rule of law. But Schlesinger, in his book “War and the American Presidency” (2004), points out that Lincoln never “claimed an inherent and routine right to do what [he] did.” The Bush White House, he told me, has seized on these historical aberrations and turned them into a doctrine of Presidential prerogative.

On September 25th, the Office of Legal Counsel issued a memo declaring that the President had inherent constitutional authority to take whatever military action he deemed necessary, not just in response to the September 11th attacks but also in the prevention of any future attacks from terrorist groups, whether they were linked to Al Qaeda or not. The memo’s broad definition of the enemy went beyond that of Congress, which, on September 14th, had passed legislation authorizing the President to use military force against “nations, organizations, or persons” directly linked to the attacks. The memo was written by John Yoo, a lawyer in the Office of Legal Counsel who worked closely with Addington, and said, in part, “The power of the President is at its zenith under the Constitution when the President is directing military operations of the armed forces, because the power of the Commander-in-Chief is assigned solely to the President.” The memo acknowledged that Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war, but argued that it was a misreading to assume that the article gives Congress the lead role in making war. Instead, the memo said, “it is beyond question that the President has the plenary Constitutional power to take such military actions as he deems necessary and appropriate to respond to the terrorist attacks upon the United States on September 11, 2001.” It concluded, “These decisions, under our Constitution, are for the President alone to make.”

Another memo sanctioned torture when the President deems it necessary; yet another claimed that there were virtually no valid legal prohibitions against the inhumane treatment of foreign prisoners held by the C.I.A. outside the U.S. Most of these decisions, according to many Administration officials who were involved in the process, were made in secrecy, and the customary interagency debate and vetting procedures were sidestepped. Addington either drafted the memos himself or advised those who were drafting them. “Addington’s fingerprints were all over these policies,” said Wilkerson, who, as Powell’s top aide, later assembled for the Secretary a dossier of internal memos detailing the decision-making process.

On November 13, 2001, an executive order setting up the military commissions was issued under Bush’s signature. The decision stunned Powell; the national-security adviser, Condoleezza Rice; the highest-ranking lawyer at the C.I.A.; and many judge advocate generals, or JAGs, the top lawyers in the military services. None of them had been consulted. Michael Chertoff, the head of the Justice Department’s criminal division, who had argued for trying terror suspects in the U.S. courts, was also bypassed. And the order surprised John Bellinger III, the National Security Council legal adviser and deputy White House counsel, who had been formally asked to help create a legal method for trying foreign terror suspects. According to multiple sources, Addington secretly usurped the process. He and a few hand-picked associates, including Bradford Berenson and Timothy Flanigan, a lawyer in the White House counsel’s office, wrote the executive order creating the commissions. Moreover, Addington did not show drafts of the order to Powell or Rice, who, the senior Administration lawyer said, was incensed when she learned about her exclusion.

The order proclaimed a state of “extraordinary emergency,” and announced that the rules for the military commissions would be dictated by the Secretary of Defense, without review by Congress or the courts. The commissions could try any foreign person the President or his representatives deemed to have “engaged in” or “abetted” or “conspired to commit” terrorism, without offering the right to seek an appeal from anyone but the President or the Secretary of Defense. Detainees would be treated “humanely,” and would be given “full and fair trials,” the order said. Yet the order continued that “it is not practicable” to apply “the principles of law and the rules of evidence generally recognized in the trial of criminal cases in the United States district courts.” The death penalty, for example, could be imposed even if there was a split verdict. Moreover, in December, 2001, the Department of Defense circulated internal memos suggesting that, in the commission system, defendants would have only limited rights to confront their accusers, see all the evidence against them, or be present during their trials. There would be no right to remain silent, and hearsay evidence would be admissible, as would evidence obtained through physical coercion. Guilt did not need to be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. The order firmly established that terrorism would henceforth be approached on a war footing, endowing the President with enhanced powers.

The precedent for the order was an arcane 1942 case, ex parte Quirin, in which Franklin Roosevelt created a military commission to try eight Nazi saboteurs who had infiltrated the United States via submarines. The Supreme Court upheld the case, 8–0, but even the conservative Justice Antonin Scalia has called it “not this Court’s finest hour.” Roosevelt was later criticized for creating a sham process. Moreover, while he used military commissions to try a handful of suspects who had already admitted their guilt, the Bush White House was proposing expanding the process to cover thousands of “enemy combatants.” It was also ignoring the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which, having codified procedures for courts-martial in 1951, had rendered Quirin out of date.

Berenson said, “The legal foundation was very strong. F.D.R.’s order establishing military commissions had been upheld by the Supreme Court. This was almost identical. What we underestimated was the extent to which the culture had shifted beneath us since World War Two.” Concerns about civil liberties and human rights, and anger over Vietnam and Watergate, he said, had turned public opinion against a strong executive branch: “But Addington thought military commissions had to be a tool at the President’s disposal.”

Rear Admiral Donald Guter, who was the Navy’s chief JAG until June, 2002, said that he and the other JAGs, who were experts in the laws of war, tried unsuccessfully to amend parts of the military-commission plan when they learned of it, days before the order was formally signed by the President. “But we were marginalized,” he said. “We were warning them that we had this long tradition of military justice, and we didn’t want to tarnish it. The treatment of detainees was a huge issue. They didn’t want to hear it.” In a 2004 report in the Times, Guter said that when he and the other JAGs told Haynes that they needed more information, Haynes replied, “No, you don’t.” (Haynes’s office offered no comment.)

At the Defense Department, Shiffrin, the deputy general counsel for intelligence, and a career lawyer rather than a political appointee, was taken aback when Haynes showed him the order. Earlier in Shiffrin’s career, at the Justice Department, his office had been in the same room where the Nazi defendants were tried, and he had become interested in the case, which he said he regarded as “one of the worst Supreme Court cases ever.” He recalled informing Haynes that he was skeptical of the Administration’s invocation of Quirin. “Gee, this is problematic,” Shiffrin told him.

Marine Major Dan Mori, the uniformed lawyer who has been assigned to defend David Hicks, one of the ten terror suspects in Guantánamo who have been charged, said of the commissions, “It was a political stunt. The Administration clearly didn’t know anything about military law or the laws of war. I think they were clueless that there even was a U.C.M.J. and a Manual for Courts-Martial! The fundamental problem is that the rules were constructed by people with a vested interest in conviction.”

Mori said that the charges against the detainees reflected a profound legal confusion. “A military commission can try only violations of the laws of war,” he said. “But the Administration’s lawyers didn’t understand this.” Under federal criminal statutes, for example, conspiring to commit terrorist acts is a crime. But, as the Nuremburg trials that followed the Second World War established, under the laws of war it is not, since all soldiers could be charged with conspiring to fight for their side. Yet, Mori said, a charge of conspiracy “is the only thing there is in many cases at Guantánamo—guilt by association. So you’ve got this big problem.” He added, “I hope that nobody confuses military justice with these ‘military commissions.’ This is a political process, set up by the civilian leadership. It’s inept, incompetent, and improper.”

Under attack from defense lawyers like Mori, the military commissions have been tied up in the courts almost since the order was issued. Bellinger and others fought to make the commissions fairer, so that they could withstand court challenges, and the Pentagon gradually softened its rules. But Administration lawyers involved in the process said that Addington resisted at every turn. He insisted, for instance, on maintaining the admissibility of statements obtained through coercion, or even torture. In meetings, he argued that officials in charge of the military commissions should be given maximum flexibility to decide whether to include such evidence. “Torture isn’t important to Addington as a scientific matter, good or bad, or whether it works or not,” the Administration lawyer, who is familiar with these debates, said. “It’s more about his philosophy of Presidential power. He thinks that if the President wants torture he should get torture. He always argued for ‘maximum flexibility.’ ”

Last month, Addington lost this internal battle. The Administration rescinded the provision allowing coerced testimony, after even the military officials overseeing the commissions supported the reform. According to a senior Administration legal adviser who participated in discussions about the commissions, Addington remained opposed to the change. “He wanted no changes,” the lawyer said. “He said the rules were good, right from the start.” Addington accused officials who were trying to reform the rules of “giving away the President’s prerogatives.”

President Bush has blamed the legal challenges for the delays in prosecuting Guantánamo detainees. But many lawyers, even some inside the Administration, believe that the challenges were inevitable, considering the dubious constitutionality of the commissions. The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Hamdan case is expected to establish whether the commissions meet basic standards of due process. The Administration lawyer isn’t sanguine about the outcome. “It shows again that Addington overreached,” he said.

Meanwhile, Addington has fought tirelessly to stem reform of other controversial aspects of the New Paradigm, such as the detention and interrogation of terror suspects. Last year, he and Cheney led an unsuccessful campaign to defeat an amendment, proposed by Senator John McCain, to ban the abusive treatment of detainees held by the military or the C.I.A. Government officials who have worked closely with Addington say he insists that legal flexibility is necessary, because of the iniquity of the enemy; moreover, he does not believe that the legal positions taken by the Bush Administration in the war on terror have damaged the country’s international reputation. “He’s a very smart guy, but he gives no credibility to those who say these policies are hurting us around the world,” the senior Administration legal adviser said. “His feeling is that there are no costs. He’ll say people are just whining. He thinks most of them would be against us no matter what.” In Addington’s view, critics of the Administration’s aggressive legal policies are just political enemies of the President.

Yet, from the start, some of the sharpest critics of detainee-treatment policies have been military and law-enforcement officials inside the Bush Administration; people close to it, like McCain; and our foreign allies. Just a few months after the Guantánamo detention centers were established, members of the Administration began receiving reports that questioned whether all the prisoners there were really, as Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had labelled them, “the worst of the worst.” Guter said that the Pentagon had originally planned to screen the suspects individually on the battlefields in Afghanistan; such “Article 5 hearings” are a provision of the Geneva Conventions. But the White House cancelled the hearings, which had been standard protocol during the previous fifty years, including in the first Gulf War. In a January 25, 2002, legal memorandum, Administration lawyers dismissed the Geneva Conventions as “obsolete,” “quaint,” and irrelevant to the war on terror. The memo was signed by Gonzales, but the Administration lawyer said he believed that “Addington and Flanigan were behind it.” The memo argued that all Taliban and Al Qaeda detainees were illegal enemy combatants, which eliminated “any argument regarding the need for case-by-case determination of P.O.W. status.” Critics claim that the lack of a careful screening process led some innocent detainees to be imprisoned. “Article 5 hearings would have cost them nothing,” the Administration lawyer, who was involved in the process, said. “They just wanted to make a point on executive power—that the President can designate them all enemy combatants if he wants to.”

Guter, the Navy JAG, said that, before long, he and other military experts began to wonder whether the reason they weren’t getting much useful intelligence from Guantánamo was that, as he puts it, “it wasn’t there.” Guter, who was in the Pentagon on September 11th, said, “I don’t have a sympathetic bone in my body for the terrorists. But I just wanted to make sure we were getting the right people—the real terrorists. And I wanted to make sure we were doing it in a way consistent with our values.”

While the JAGs’ questions about the treatment of detainees went largely unheeded, he said, the C.I.A. was simultaneously raising similar concerns. In the summer of 2002, the agency had sent an Arabic-speaking analyst to Guantánamo to find out why more intelligence wasn’t being collected, and, after interviewing several dozen prisoners, he had come back with bad news: more than half the detainees, he believed, didn’t belong there. He wrote a devastating classified report, which reached General John Gordon, the deputy national-security adviser for combatting terrorism. In a series of meetings at the White House, Gordon, Bellinger, and other officials warned Addington and Gonzales that potentially innocent people had been locked up in Guantánamo and would be indefinitely. “This is a violation of basic notions of American fairness,” Gordon and Bellinger argued. “Isn’t that what we’re about as a country?” Addington’s response, sources familiar with the meetings said, was “These are ‘enemy combatants.’ Please use that term. They’ve all been through a screening process. We don’t have anything to talk about.”

A former Administration official said of Addington’s response, “It seemed illogical. How could you deny the possibility that one or more people were locked up who shouldn’t be? There were old people, sick people—why do we want to keep them?” At the meeting, Gordon and Bellinger argued, “The American public understands that wars are confusing and exceptional things happen. But the American public will expect some due process.”

Addington and Gonzales dismissed this concern. The former Administration official recalled that Addington was “the dominant voice. It was a non-debate, in his view.” The confrontation made clear, though, that Addington had been informed early that there were problems at Guantánamo. “There wasn’t a lack of knowledge or understanding,” the former official said.

Addington has proved deft at outmaneuvering his critics. Documents embarrassing to Addington’s opponents have been leaked to the press, if not necessarily by him. A top-secret N.S.C. memo describing Powell’s request to reconsider the suspension of the Geneva Conventions appeared in the Washington Times the day after it was circulated to the Secretary of Defense, the Attorney General, and the Vice-President; the article cited unnamed sources who accused Powell of “bowing to pressure from the political left.” The Administration lawyer said, “The way Addington works, he controls the flow of information very tightly.” Addington chastised a Justice Department official who showed a legal opinion on the treatment of detainees to the State Department. He repeatedly directed Gonzales, the White House counsel, to keep Bellinger, the N.S.C. lawyer, out of meetings about national-security issues. “Lip-lock” is the word Addington’s old Pentagon colleague Sean O’Keefe, now the chancellor of Louisiana State University, used to describe his discretion. “He’s like Cheney,” O’Keefe said. “You can’t get anything out of him with a crowbar.” The Administration lawyer said, “He’s a bully, pure and simple.” Several talented top lawyers who challenged Addington on important legal matters concerning the war on terror, including Patrick Philbin, James Comey, and Jack Goldsmith, left the Administration under stressful circumstances. Other reform-minded government lawyers who clashed with Addington, including Bellinger and Matthew Waxman, both of whom were at the N.S.C. during Bush’s first term, have moved to the State Department.

Waxman, a young lawyer who headed the Pentagon’s office of detainee affairs, departed soon after he had a major confrontation with Addington over the issue of clarifying military rules for the treatment of prisoners. Waxman believed that international standards for the humane treatment of detainees should be followed, and argued for reforms in the Army Field Manual. He hoped to reinstate the basic standards that are specified in the Geneva Conventions. This meant the prohibition of torture, overt acts of violence, and “outrages on personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment.” Although the Vice-President’s office is not part of the military chain of command, last September Addington summoned Waxman to his office and berated him. Waxman declined to comment on the incident, but a former colleague in the Pentagon, in whom Waxman confided, said that Addington accused Waxman of wanting to fight the war on terror his own way, rather than the President’s way. The Army Field Manual still hasn’t been revised, and, according to those involved, Addington and his protégé Haynes remain the major obstacles.

Last fall, Richard Shiffrin, the Pentagon lawyer who was left out of the Administration’s initial discussions of the military commissions, learned from the Times about the Administration’s decision to sanction warrantless domestic electronic surveillance by the National Security Agency. This was remarkable, because Shiffrin was the Pentagon lawyer in charge of supervising the N.S.A.’s legal advisers. “It was exceptional that I didn’t know about it—extraordinary,” Shiffrin said. “In the prior Administration, on anything involving N.S.A. legal issues I’d have been made aware. And I should have been in this one.”

Shortly after September 11th, Addington and Cheney, without alerting Shiffrin, held meetings with top N.S.A. lawyers in the Vice-President’s office and told them that the President, as Commander-in-Chief, had the authority to override the FISA statutes and not seek warrants from the special court. According to the Times, Addington and Cheney pushed the N.S.A. to engage in practices that the agency thought were illegal, such as the warrantless wiretapping of American suspects making domestic calls. General Michael Hayden, the former head of the N.S.A., who was recently confirmed as director of the C.I.A., has denied being pressured. Shiffrin, however, doubted that the N.S.A. lawyers were expert enough in Article II of the Constitution, which defines the President’s powers, to argue back. He described the Administration’s legal arguments on wiretapping as “close calls.”

Others are more critical. Fourteen prominent constitutional scholars, representing a range of political views, recently wrote an open letter to Congress, claiming that the N.S.A. surveillance program “appears on its face to violate existing law.” The scholars noted that Bush had made no effort to amend the FISA law to suit national-security needs—he simply ignored it. The Republican legal activist Bruce Fein said, “What makes this so sinister is that the members of this Administration have unchecked power. They don’t care if the wiretapping is legal or not.” But the former high-ranking Administration lawyer suggested that the situation is more serious than an intentional infraction of the law. “It’s not that they think they’re skirting the law,” he said. “They think that this is the law.”

Fein suggested that the only way Congress will be able to reassert its power is by cutting off funds to the executive branch for programs that it thinks are illegal. But this approach has been tried, and here, too, Addington has had the last word. John Murtha, the ranking Democrat on the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense, put a provision in the Pentagon’s appropriations bills for 2005 and 2006 forbidding the use of federal funds for any intelligence-gathering that violates the Fourth Amendment, which protects the privacy of American citizens. The White House, however, took exception to Congress’s effort to cut off funds. When President Bush signed the appropriations bills into law, he appended “signing statements” asserting that the Commander-in-Chief had the right to collect intelligence in any way he deemed necessary. The signing statement for the 2005 budget, for instance, noted that the executive branch would “construe” the spending limit only “in a manner consistent with the President’s constitutional authority as Commander-in-Chief, including for the conduct of intelligence operations.”

According to the Boston Globe, Addington has been the “leading architect” of these signing statements, which have been added to more than seven hundred and fifty laws. He reportedly scrutinizes every bill before President Bush signs it, searching for any language that might impinge on Presidential power. These wars of words are yet another battlefront between Addington and Congress, and some constitutional scholars find them troubling. Few of the signing statements were noticed until one of them was slipped into Bush’s signing of the McCain amendment. The language was legal boilerplate, reserving the right to construe the legislation only as it was consistent with the Constitution. But, considering that Cheney’s office had waged, and lost, a public fight to defeat the McCain amendment democratically—the vote in the Senate was 90–9—the signing statement seemed sneaky and subversive.

Earlier this month, the American Bar Association voted to investigate whether President Bush had exceeded his constitutional authority by reserving the right to ignore portions of laws that he has signed. Richard Epstein, the University of Chicago law professor, said, “What’s frightening to me is that this Administration is always willing to push the conventions to the limits—and beyond. With his signing statements, I think the President just goes too far. If you sign these things with a caveat, do the inferior officers follow the law or the caveat?”

Bruce Fein argues that Addington’s signing statements are “unconstitutional as a strategy,” because the Founding Fathers wanted Presidents to veto legislation openly if they thought the bills were unconstitutional. Bush has not vetoed a single bill since taking office. “It’s part of the balancing process,” Fein said. “It’s about accountability. If you veto something, everyone knows where you stand. But this President wants to do it sotto voce. He wants to give the image that he’s accommodating on torture, and then reserves the right to torture anyway.”

David Addington is a satisfactory lawyer, Fein said, but a less than satisfactory student of American history, which, for a public servant of his influence, matters more. “If you read the Federalist Papers, you can see how rich in history they are,” he said. “The Founders really understood the history of what people did with power, going back to Greek and Roman and Biblical times. Our political heritage is to be skeptical of executive power, because, in particular, there was skepticism of King George III. But Cheney and Addington are not students of history. If they were, they’d know that the Founding Fathers would be shocked by what they’ve done.”

Mirror image

Could Iraq be Vietnam in reverse? What George F. Kennan's 1966 Senate testimony can tell us about Iraq in 2006.

``DO YOU SEE, as some of your critics do, a parallel between what's going on in Iraq now and Vietnam?" President George W. Bush was asked at a press conference earlier this month. The president, unsurprisingly, responded ``No." ``Because there's a duly-elected government; 12 million people voted," he said. ``Obviously, there is sectarian violence, but this is, in many ways, religious in nature, and I don't see the parallels."

It is possible to quibble with the president's explanation. There was religious unrest in Vietnam in 1963, when Buddhists protested the Christian-led government, and South Vietnam held presidential elections in 1967. Yet President Bush is right on the larger point: Iraq is not Vietnam. Of course, detractors have long compared the two conflicts in order to suggest that the war in Iraq is an unwinnable quagmire. But if anything, the war in Iraq looks like the Vietnam War in reverse.

Consider the respective arcs of the two conflicts. In Vietnam, the United States entered a divided country with a simmering civil war and left behind a nasty tyranny. In Iraq, the US has unseated a nasty tyranny but may leave behind a simmering civil war that could lead to a divided country. In Vietnam, fearing a nuclear clash with the Soviet Union or a confrontation with China, the US slid in slowly: first sending technical advisers, then undertaking search and destroy missions, and ultimately engaging in a full-throttle war. In Iraq, the US began full throttle, switched to search and destroy, and is now seriously debating whether to begin sliding out. In Vietnam, America was fighting to uproot communism. Now, it's fighting to plant democracy.

By this logic, the situation in Iraq today should be compared to the winter of 1966, when the US was about a year into major troop deployments in Vietnam. In 1966, America had a bit more than 150,000 troops engaged; now the US has just under that number. In both cases, about 2,500 soldiers had already died in action. This week, the Senate has held its first major hearings on the war since serious fighting began. The same thing happened regarding Vietnam in February of 1966. And it is these 1966 hearings-in particular the testimony of George F. Kennan, the framer of America's Cold War ``containment" policy-which offer vital insight into the current situation in Mesopotamia.

. . .

In 1964, after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, Arkansas Senator and Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee William Fulbright voted in favor of escalating the war in Vietnam. By 1966, however, he had begun to change his mind. He convened a hearing before his committee to debate the issue, calling Kennan, among others.

Kennan was likely chosen because of a recent article he'd written for The

Kennan opened with a statement that likely resonates with many Americans today. If not already involved in the war, he said, ``I would know of no reason why we should wish to become so involved, and I could think of several reasons why we should wish not to." Recent opinion polls show that far fewer Americans would have supported attacking Iraq three years ago if they'd known how much it would cost in dollars and lives, the strength of the insurgency it would inspire, and of course how few threatening weapons Saddam Hussein actually had.

As a foreign policy realist, and a longtime skeptic of America's ability to change the world for the better, Kennan made the case that the only legitimate reason for staying in Vietnam was the fear that an abrupt departure might harm our reputation and make a bad situation worse. ``A precipitate and disorderly withdrawal could represent in present circumstances a disservice to our own interests, and even to world peace," Kennan said. President Bush and others have made a similar case for staying the course in Iraq. ``If we fail in Iraq, it's going to embolden al Qaeda types. It will weaken the resolve of moderate nations to stand up to the Islamic fascists. It will cause people to lose their nerve and not stay strong," he said at the same press conference where he was asked about similarities between Vietnam and Iraq.

Kennan, however, took knives to the argument that leaving meant showing weakness. He pointed out the waste of American resources in Vietnam, and the cost of focusing so much attention on one remote country. Again, the same has been said of Iraq. The invasion has won the United States few friends, and many enemies, cost hundreds of billions of dollars, and distracted us from other issues-including serious problems in Russia, Iran, and North Korea, and the ongoing fight against al Qaeda. ``However justified our action may be in our own eyes, it has failed to win either enthusiasm or confidence, even among peoples normally friendly to us," Kennan said.

Kennan articulated a plan whereby America would switch from offense to defense in Vietnam, and begin to seek a peace settlement- even on terms less desirable than its initial objectives. ``[T]here is more respect to be won in the opinion of this world by a resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions than by the most stubborn pursuit of extravagant and unpromising objectives," he said. Kennan, were he alive today, would have little patience for the Bush administration's frequent call to stay in Iraq because a commitment was made and so many soldiers have already died. Just because the US had shot itself in one foot, he told the Senate committee, didn't mean it should fire away at the other.

. . .

Kennan concluded his Senate testimony with a well-known quotation from John Quincy Adams. ``[America] goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy," said our sixth president. ``She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own."

Kennan used Adams's words to argue for a brand of realism necessary when the country overextends itself, as many today argue the Bush administration has.

Since the United States became the world's most powerful nation, it has constantly oscillated between idealism and realism. The idealists try to remake the world in our image; their successors pull back, focusing on issues at home and negotiating international affairs more cautiously. Eisenhower put on the brakes after Harry Truman declared that this country would do anything in support of democracy. Despite Kennan's best efforts, it would take Richard Nixon's détente to snuff the ``bear any burden" approach of the Kennedy and Johnson years.