Thursday, May 18, 2006

Kentucky Gov Ernie Fletcher Indicted. The words "Republican Indicted" seem to go together often these days. Must be those "family values."

Monster Mash: Governors vs. Attorneys General - Chandler says Fletcher ‘Guilty of Fraud on the Public’

Monster Mash: Governors vs. Attorneys General - Chandler says Fletcher ‘Guilty of Fraud on the Public’By Michael Lindenberger

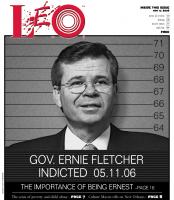

Happy anniversary, Governor Fletcher. Almost a year to the day after it began investigating Fletcher’s administration for alleged violations of state law regarding the merit system, the grand jury indicted Fletcher on one count each of criminal conspiracy, first-degree official misconduct and violation of the prohibition against political discrimination. The charges were gift-wrapped by Attorney General Greg Stumbo, who did not include a Get Out of Jail Free card.

Maybe by design, and maybe not, the indictments were announced the Thursday just after the Derby and just before the Primary Elections, a period when many Kentuckians already are suffering from sensory overload.

Gov. Ernie Fletcher’s angry reaction to his indictments last week had a familiar ring to anyone who paid attention to the end stages of his embattled predecessor’s tenure.

On Friday, Fletcher denounced the indictments as mere political maneuvering by a man — Stumbo — who is widely considered a likely candidate for governor in 2007.

But just three years ago, it was Fletcher’s predecessor — the man whose example Fletcher blasted at every campaign stop — who was savaging an attorney general for what he called ruthless political opportunism.

In June of his last year in office, then-Gov. Paul Patton pardoned four men, including his chief of staff, who had been indicted for allegedly violating the state’s campaign finance laws during Patton’s bitter 1995 contest against Republican Larry Forgy. After his defeat, Forgy filed a complaint with then-Attorney General Ben Chandler, prompting a case that drug on nearly eight years.

“It was obvious from day one that Ben Chandler was looking at this as an opportunity to put Paul Patton in prison,” Patton said at the time, explaining the pardons. “You’ve got innocent people being persecuted and prosecuted by a politically ambitious candidate for governor; that’s an unprecedented situation.”

In response, Chandler, a Democrat by then running against Fletcher for governor, immediately called for Patton to resign.

On Friday, Fletcher was reading from Patton’s playbook, rather than the clean-up-the-mess-in-Frankfort script he used during his campaign.

On Saturday, his spokesman repeated Fletcher’s charges against Stumbo in an interview.

“We’re talking about Greg Stumbo, the most partisan Democrat in modern Kentucky history,” said Brett Hall, Fletcher’s communications director. “He’s a very wily and skillful political operator … (who is) bored with the mundane work an attorney general has to do, like bringing drug dealers to justice, focusing on deadbeat dads and finding welfare cheats.”

To press that charge into the legal arena, Fletcher’s lawyers filed a motion in Franklin Circuit Court asking that Stumbo and his entire office be removed from the case, citing a conflict of interest, given his potential run for governor next year.

Vicki Glass, a spokesman for Stumbo, called the motion “baseless,” adding that “political corruption” is precisely the kinds of cases attorneys general are elected to pursue.

“The only person running for governor is Ernie Fletcher,” she said, repeating remarks made by Stumbo the day before.

Over the weekend, Chandler, now a congressman who said he has not ruled out a repeat campaign for governor, said Stumbo would have to withdraw from the case — if he had officially filed to run against Fletcher in 2007. But since Stumbo has only said he is considering the race, the ethics rules for prosecutors and executive branch officials prohibiting conflicts of interest wouldn’t apply, Chandler said.

“I think that, if there was an immediate conflict of interest, he would step aside from the case — if there were that conflict,” Chandler said Saturday. “But you have to understand the legal definition of a conflict — it’s a present conflict, not a potential one.”

(On Monday, in a statement broadcast on television, Stumbo said he would not file to oppose Fletcher for governor, so long as the investigation continues.)

Besides, Chandler said, Stumbo is simply doing what he was elected to do.

“Having been there myself as attorney general, I’d ask, ‘What can he do, other than his job?’ You have to follow the law,” Chandler said. “This idea that he is just leading the grand jury around the room by the nose is nonsense. When I was pursuing indictments, they called me to testify — and I was the one who empanelled them. … Patton said the same thing about me … that I was on a witch hunt, trying to put him in jail — that it was all politics.”

Patton, in an interview on Monday, defended his pardons — but said he would not comment on Fletcher’s indictments. His successor deserves to lead Kentucky without taking any “cheap shots” from the man he replaced, he said.

Generally, Patton said, there are enough career staff members in the Office of the Attorney General to head off a purely political prosecution. “Someone is going to stand up and object,” he said.

An attorney general has to investigate accusations of public wrong-doing, he added.

Still, he said, politics can play a role. He said he believes top prosecutors in Chandler’s office objected to Chandler’s hardball pursuit of the investigation into possible campaign irregularities, but that Chandler overruled them.

“With the General Chandler situation in particular, I asked him to investigate charges of vote-buying that Larry Forgy had made (following the 1995 election). The state police had already determined that there was no evidence of vote-buying, and Attorney General Chandler, to my knowledge, never turned up any evidence of vote-buying anyplace. But he took off on a totally differently tangent.”

That tangent involved untested provisions of the 1992 campaign-finance law. On Saturday, however, Chandler said that he, like Stumbo, had only been following the law.

“I see a lot of similarities between what Fletcher is saying now and what we heard from Patton,” said Chandler, who added he enjoys his work in Congress but won’t rule out running for governor again. “What he is saying now is what everybody says who is charged with an infraction or a crime. You can just script it.”

Chandler said he took flak from many, including Fletcher during the campaign, for not pursuing an indictment against Patton instead of just two of the governor’s top aides and two labor-union leaders.

But Chandler said prosecutors can only pursue cases as far as their evidence takes them. He said suggestions that Patton’s team also violated merit employee rules were made during his time as attorney general — but said his office never received the kind of evidence that Stumbo is working with.

“We had no similar allegations,” he said. “Nobody brought me anything like what Stumbo has received. In this case, the whistle-blower, Doug Doerting, brought Stumbo some 250 pages of very carefully documented material. We never received anything close to that.”

Patton isn’t the only former living governor to have endured an investigation while in office.

Former Gov. Julian Carroll, who served five years in the 1970s, was also investigated and saw a close associate, Kentucky Democratic Party Chairman Howard “Sonny” Hunt, go to federal prison on charges stemming from an insurance scam. Carroll, best known now for his swept-back white hair and booming oratorical style, was elected to the State Senate in 2004. He called Fletcher’s charges that the charges are driven by politics “absolutely ludicrous.”

“You start with the simple fact that the attorney general did not start this investigation,” Carroll said. “A whistle-blower did, when he brought claims of a violation of the law. Had the attorney general refused to act, then he would have been guilty of misfeasance in office. … The governor’s charges are so ludicrous. … It simply hasn’t happened.”

Carroll said Fletcher’s defiance of the charges, more than any actual wrong-doing, has doomed his governorship.

That defiance has included issuing pardons for 13 current or former members of his administration and an attempt to have a judge order the grand jury’s job completed before its term expired.

On Saturday, Hall conceded that the Fletcher administration had been under great pressure by supporters in Republican-dominated areas of the state to put party members on the state payroll.

“There were places that were 80-percent Republican, where the local complaint was that Democrats were always getting the jobs,” he said, adding that the party loyalists wanted to correct that imbalance. “But we resisted that pressure.

“We never went there,” Hall said. “Every time it was discussed, it was made clear, each and every time, that merit jobs were off limits.”

Hall also said it’s revealing that this is the first time that violations of the hiring laws have resulted in indictments, rather than being handled as complaints to the personnel board or the Executive Branch Ethics Commission.

“A lot of people have told us that were the governor and Greg Stumbo of the same party, he would have never gone down this road,” Hall said.

Carroll argues that by fighting the charges so stubbornly, Fletcher has forced himself into a corner where his only option left is to attack the motivation of the prosecutor.

“He could say, ‘No, I didn’t do it,’ but the evidence is going to contradict that,” Carroll said. “All he can say is, ‘This is political.’ He has used the only course of action that is open to him. He is going to get a few people out in the state to believe that, but there is not going to be many.”

Carroll said he believes Fletcher could head off a trial, and possible jail sentence, if he stepped forward and admitted unintentional wrong-doing, and accepted a minor reprimand.

But no matter what, he said, the indictments have ruined any chances for a second term.

“This has damaged the governor beyond repair,” said Carroll, his own political ressurection notwithstanding. “He’s already been polling 32- and 33-percent approval for nearly a year. You can’t run a statewide race with a 32 positive. Republicans for some time have been looking for another candidate. A member of the governor’s staff has told me that they expect that when he starts trying to raise money, he’s going to get the message.”

Chandler, too, said Fletcher’s insistence that the charges are mere politics may not insulate him from voters who feel betrayed.

“I think everybody in the state is somewhat surprised by this ultimate outcome,” Chandler said. “In my opinion, he’s guilty of a fraud on the public. He ran his entire campaign on the theme of cleaning up the mess in Frankfort. He talked repeatedly about doing things differently, his rock-solid values and getting rid of the old-boy network. But what they’ve done is use everything in their power to replace one old-boy network with a new one.”

But Fletcher won’t have to face the voters for another year. In the meantime, one wonders where his support is coming from. Certainly not Sen. Mitch McConnell. Not Senate President David Williams. And not, apparently, from the state party itself.

“We are not commenting on the indictment at all,” said Michael Clingaman, executive director of the Republican Party of Kentucky. “Unless you want to talk about the 2006 races, we just aren’t going to comment.”

Could this reluctance stem from Fletcher’s failed attempt to replace the party chairman last year?

“I am not commenting on that, either,” he said, adding that he also wouldn’t comment on whether state and congressional candidates for the 2006 election are worried about the fallout of the indictments in their races.

“We’re focusing on raising money, and putting our candidates in a position to win their election, no matter what environment they are running in,” Clingaman said.

But whatever the voters decide, even Patton, Chandler’s scandal-plagued nemesis, suggested that the “it’s-all-politics” defense is a weak one when fighting criminal charges by elected politicians.

He said despite good intentions, every politician makes mistakes — sometimes mistakes their opponents view as criminal. But it’s that very scrutiny that helps wise politicians make mid-course corrections, he said.

“It’s that adversarial system — between those governing and the press, and between the political opponents — that keeps the system working efficiently,” Patton said. “Even in our case, say with the campaign finance situation, we didn’t think we did anything wrong. But you better believe that it is that adversarial system that makes you aware of it the next time, and you do do things differently the next time.”

Right now, with a date in court, the challenge for Fletcher and his supporters is to figure out how to manage their adversaries long enough to get a chance to have a “next time